(Want to see next month’s edition early? Follow this GitHub repo for the latest updates and early looks at the newsletter as it’s written - Also check out my LinkedIn!)

This month’s updates:

GigaIO introduces a 32-GPU server (single node) solution

HPE x NREL complete the Kestrel supercomputer with 528 Nvidia H100 GPUs

Nvidia’s Blackwell (B100) cards delayed/cancelled.

Nvidia B200"A" cards and an air-cooled NVL36 (36-GPU rack) announced

IBM announces Tellum-II and Spyre chips

One-pagers:

ConnectX-7

NCCLs

Spine-Leaf topology

This month's updates:

GigaIO - SuperNODE

A small American OEM, GigaIO has made headlines in quite a few HPC publications about its 32-GPU server - That’s 32 GPUs, acting as if they are within a single chassis. Depending on the implementation details and what's technically sound vs what's just marketing, this might be a great product.

For large workloads that must be distributed across multiple servers, a lot of communications hardware (networking) is needed to let CPUs and GPUs (compute) send data back and forth. However, sending data further away from compute will always be a slow and relatively inefficient process.

Efforts to remove the networking for small-medium sized clusters1 (32 to 256 GPUs) have shown some success, and in the case of GigaIO, profits too, with TensorWave (a GPUaaS provider) now working with GigaIO on a 5000+ GPU cluster.

GigaIO's FabreX technology, a PCIe-based interconnect that allows various components of a server (or multiple servers) to aggregate into one virtual server and talk to each other. This can extend over multiple racks, allowing for the possibility of having 1000s of GPUs Hyperconverged via one interconnect.

32 GPUs + 16 CPUs spread across 4 physical servers, connected via FabreX, acting as one physical server. This does mean that the connections between all GPUs are not equal in length, and so significant latency differences may be an issue.

Kestrel – U.S. Public sector's new supercomputer

NREL (National Renewable energy Lab) launched a GPU-enabled supercomputer, with 528 Nvidia H100 GPUs, opening it up for use on U.S. government energy and renewables projects. A big win for HPE for sure, but an even bigger win for Ethernet.

132 HPE Cray XE servers, 4x H100 + 2x AMD Genoa each

44 PetaFLOPs of aggregated compute

384GB (350 effectively) RAM and 3.2TB storage per server

Using HPE's slingshot 11 fabric for networking (200GbE)

Supporting U.S. Dep. Of Energy and EERE (Renewables)

Using HPE's Slingshot 11 fabric for its networking solution, NREL decided to stick to Ethernet rather than adopting the InfiniBand standard that Nvidia is pushing. The Slingshot tech stack is a proven and capable ethernet networking solution, using HPE's switches and RoCE with additional features such as adaptive routing and congestion control to create an efficient and fast network that approaches InfiniBand's realised latencies and throughputs. This is another data point supporting the trend of industry moving towards ethernet and refusing to pay premiums for InfiniBand and be locked-in to Nvidia's technology ecosystem.

Nvidia B100s delayed/cancelled

Due to issues with manufacturing and packaging the silicon itself at TSMC, Nvidia are being forced to delay shipments of the B200, and possibly even cancelling the B100. Depending on who is asked, research into denser and more power-hungry semiconductors is either going fine or reaching a saturation point, but regardless of which you believe, evidence shows that we are starting to see some issues.

TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor) and Nvidia had agreed to a very aggressive schedule of producing over a million chips per quarter for the BX00 and GBX00 line-ups, but due to issues with the novel techniques being used to put the chips together and onto the motherboards, Nvidia have been forced to delay their plans to meet customer demands for B100 and B200 chips. This has knock on effects of course for the planned GB200 NVL36/72 (Grace CPU + Blackwell GPU servers, rack of 36 or 72 GPUS total), but they seem to have kept their plans for the B200 Ultra GPUs, the denser and more compute intensive versions of the B200s. How customers who have huge orders such as Meta and Tesla will react to this, we are yet to see, but its certain that the already deployed HX00 and GHX00 line-up's lifespans have been extended to accommodate these delays.

Nvidia's new B200"A" and Air-cooled NVL36

Either in response to the BX00/GBX00 delays, or as was always planned, Nvidia have announced two new products, showing that they are indeed listening and responding to market demands: The B200A reduced capability GPU, and the GB200A NVL36/72 copper-connected air-cooled racks.

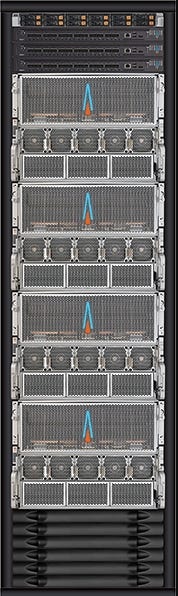

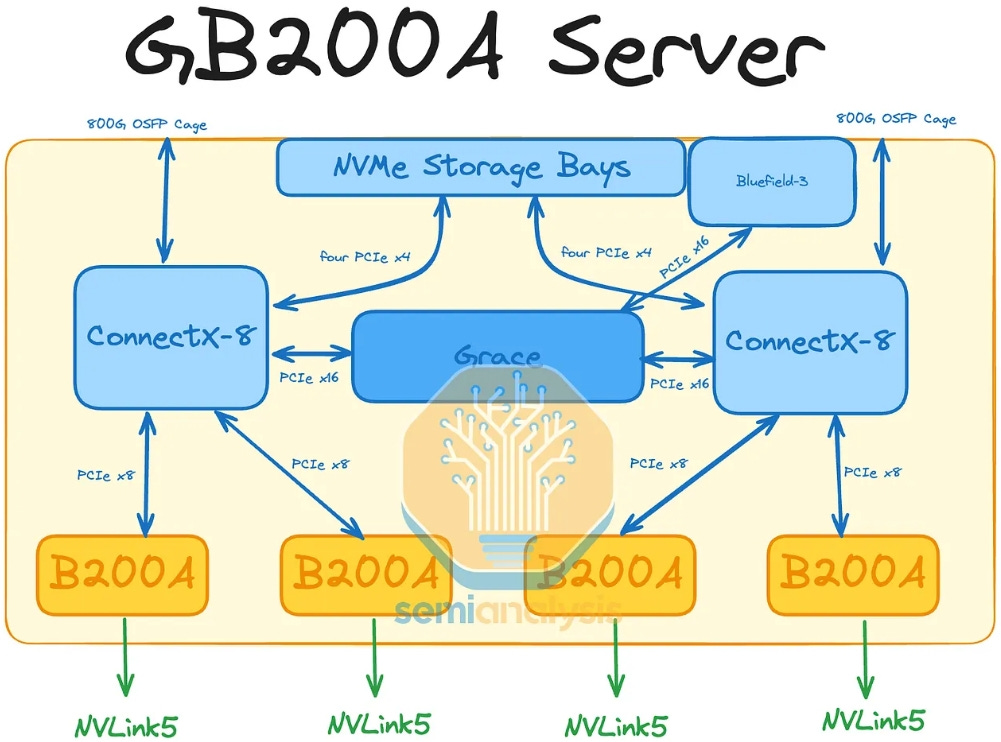

The GB200A is designed to have a lower TDP (thermal design power), and hence even 2RU dense compute units containing 4 of these (diagram below) can be air-cooled without loss of performance, allowing customers who don’t have liquid-cooling capable infrastructure to find a compromise between cutting edge products from Nvidia and costs/capabilities. In addition, using the NVLink gen5 GPU-GPU interconnect, as well as their new NVLink switches for connecting multiple NVLink-capable GPUs, Nvidia can now offer a fully copper-connected 9-server rack, completely avoiding optics (and the associated additional parts and costs), with the NVLink switches also being extensible up to 576 GPUs, potentially resulting in an InfiniBand/Ethernet-free small/medium GPU cluster.

GB200A NVL36 – NVLink connected 9 Grace CPU and 36 B200A GPU air cooled rack, containing 9 compute trays with 4 GPUs each, as well as 9 NVLink middle-of-rack switches, resulting in a fully copper connected, air cooled multi-node rack. Nvidia has understood that liquid cooling, high-bandwidth networking, and excessive power densities are roadblocks to customers adopting their latest products and have adapted accordingly.

IBM's new Tellum-II and Spyre

At Hotchips 2024, IBM announced two new chips for its latest push into high-performance AI inference. The Tellum-II CPU, and the Spyre AI accelerator. As usual for IBM, they're pushing on energy efficiency, smarter compute units, and larger caches instead of the power-hungry HBM approach Nvidia and AMD are taking

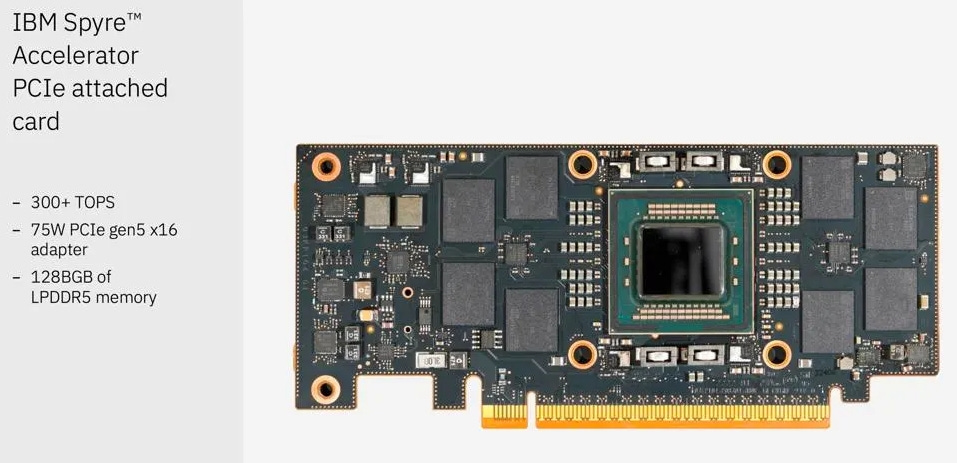

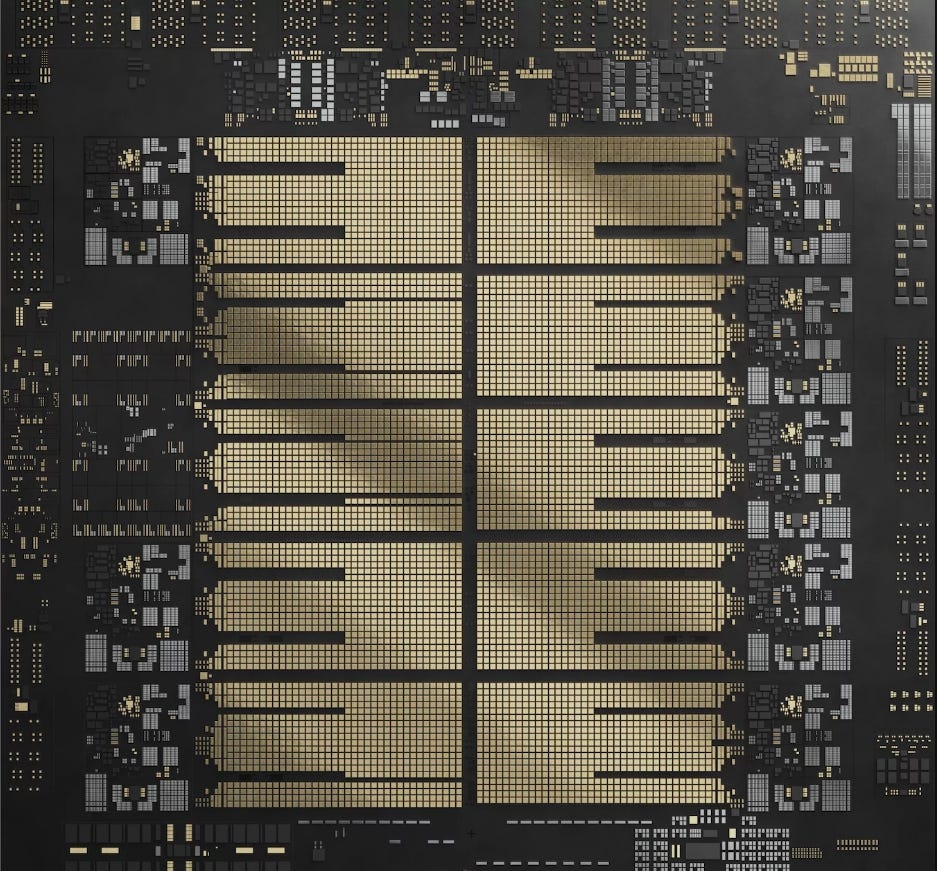

The Spyre AI accelerator chip (not yet named as a GPU/NPU or otherwise) is a PCIe form-factor, 75W, 300TOPs card is IBM's official push into generative AI hardware, focusing on efficient low-precision floating point compute, PCIe compatibility for ease of adoption by OEMs, and surprisingly (pleasantly so though), LPDDR5 instead of HBM. The decision to go with low-power DDR Gen5 RAM instead of high-bandwidth memory like Nvidia and AMD have, points to IBMs commitment to avoid excessive power-density. They might attempt to mitigate the lower bandwidth with larger L2/VL3 caches or even adding an VL4 cache like the Tellum-II does, but this has not been confirmed yet.

The Tellum-II CPU is a major improvement over the first version, with the key upgrades being: 5.5GHz frequency (very high), 10x36MB L2 cache (quite large), 360MB and 2.8GB virtual L3 and L4 caches (wow), an integrated 24 TOPs AI accelerator unit, and an enhanced DPU with its own dedicated L2 cache! All of these add up to the Tellum-II being a very capable CPU, pairing IBM's famous reliability with decent AI inferencing performance. It's intended for traditional ML and light AI workloads, though paired with the Spyre AI accelerators, IBM have the potential for making competitive 4-6U compute trays (almost definitely air-cooled due to the low TDP they’ll have) with 8 accelerators like the offerings that OEMs like Dell and HPE provide for Nvidia/AMD GPUs.

One-pagers:

ConnectX-7

Pre-training (from scratch) large language models (LLM) is orders of magnitude more computationally expensive than finetuning them, and so using a single server isn't practical. But to scale beyond the chassis, AI cards like GPUs need to start networking – They need network interface cards (NICs).

Basic functionality:

1 - Takes data from GPUs/CPUs into its own memory

2 - Wraps data into "packets" to be sent over a network

3 – Serialises (converts into binary 0/1s) the packets

4 – Sends and receives packets

5 - Reverses the above work at the destination

All the above, up to a theoretical 400Gbps (50GB/s)

Without NICs like connectX-7 or its competitors, you would need to either:

Not use the network (restrict your work to one server)

OR

Expand a single server to accommodate all the GPUs in your entire cluster (difficult/impossible)

NCCL-testing a datacentre

Once a datacentre has been racked and cabled, how do we know that all the parts are talking to each other properly? For Nvidia servers, its best to use the very same technology that enables large-scale distributed AI training and inference – Nvidia's Collective Communications Library (NCCL)

NCCL is Nvidia's software library for efficient and easy to use communications between multiple GPUs on the same network, whether within the same server or in a different rack. Once all the cabling is done, its NCCL that AI engineers will use to distribute the AI model training and inferencing across the datacentre.

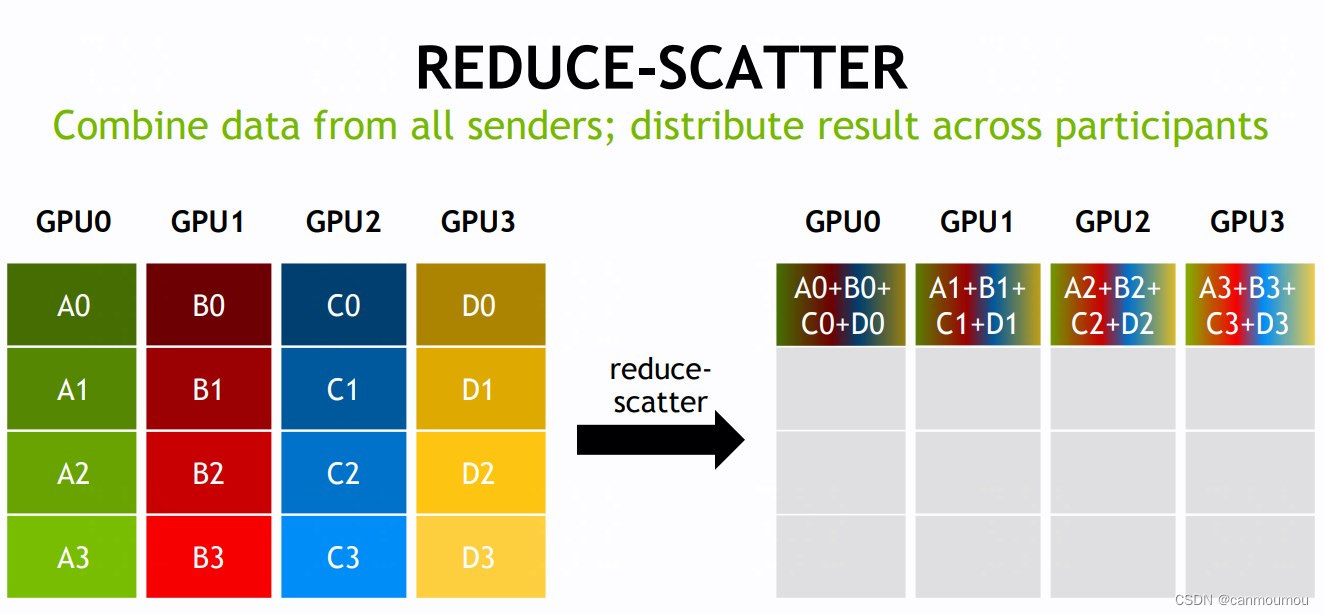

NCCL’s “gather” and “reduce-scatter” functions, two of the many collective communication functions that NCCL provides. Diagrams show how NCCL can take data distributed across multiple GPUs and organise and optimise multiple send/receive operations simultaneously to achieve whatever end data pattern is required.

Why is this important for testing? Since NCCL handles communication patterns of many kinds, it's easy to test all of these to see is every combination of cables are configured correctly. Setting up some simple checks to see if the data before and after the transfers are what you'd expect will let you know if there might be issues in your networking and can also help diagnose them.

Spine-leaf topology

When networking multiple nodes in a datacentre, there are many options available to designers on how to connect sets of nodes together to optimise for varying objectives: uplink/downlink bandwidth, symmetry, cost, and many more. But when scaling to a 100,000 GPUs, spine-leaf topologies are likely the best bet.

Because network switches like the those from Arista or Juniper have so many ports at such high bandwidths (64 x 800GbE are available now, 144 port versions and 1.6TbE per port versions coming soon), E-W network topologies can be quite varied and optimised for particular goals or use cases. However out of all the options available, the spine-leaf setup has been quite popular recently for AI clusters, for a few key reasons:

Extensible up to 100,000+ GPUs or flexible to support multiple concurrent layer 2s/3s

Enables non-blocking (same upload and download rates) communication between all devices on network, ensuring high bandwidth without bottlenecks

Guarantees that all devices under a leaf node are 2 hops away from each other, reducing latency

Reduces the number of switches required whilst maintaining performance, keeping costs under control

In a classic spine-leaf topology, each of the leaf nodes (individual servers or a rack) are connected to each of the spine switches, allowing every node to talk to any other with a maximum of 2 hops. While this means that there will be fewer cables on any given physical path between two leaf switches, multiple paths (red) using all spine switches can be used to network between the same two pair of leaf switches, resulting in high aggregate bandwidth if the pathing and congestion are managed well by software.

(Want to see next month’s edition early? Follow this GitHub repo for the latest updates and early looks at the newsletter as it’s written - Also check out my LinkedIn!)